TIME Magazine named those treating Ebola patients as its 2014 Person of the Year. Joel Selanikio is one of them.

“I knew I was going to go,” Selanikio tells us from his base in Lunsar, Sierra Leone, where he is currently treating Ebola patients.

“If you’re a firefighter and you walk past a building on fire, what’s your first thought? Do you think, ‘Should I respond?’ or do you think, ‘I am perfectly qualified to respond to this?’”

Selanikio is a pediatrician at Georgetown University Hospital and a former epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control. (In the interests of full disclosure, he was also a backer of our Kickstarter campaign last year.) Despite Selanikio’s credentials, he admits it’s been tough to gauge which Ebola patients will survive.

One morning, Selanikio approached a woman who was lying in bed and shook her shoulder. “Her eyes were open,” he said, “but she was gone.” He had spoken to the woman the day before, and she had seemed fine. “It’s confounding for doctors – for me – when you see that your idea of how a patient is doing is completely wrong, and deadly wrong.”

There have been many setbacks in the world’s efforts to combat Ebola. The most recent statistics from the Centers for Disease Control put the death toll over 8,000. When Selanikio looks to the future, he says he is optimistic about Ebola but deeply troubled about the bigger picture in West Africa. “I’m pretty sure by this time next year we will have mopped this up pretty well. I’m also sure that by this time next year Sierra Leone will be in the very sad state it’s in otherwise. And so will Liberia.”

Selanikio praises the gains that global health has achieved over the years, combating serious diseases like polio, small pox and measles. But when he looks for similar progress in international development more broadly, Selanikio says there is little to praise.

“Where are the successes?” he asks. “Where is there a poor country that is now less poor as a result of the intervention performed by, or funded by, an international development agency?”

Selanikio says the failures of international development to eradicate extreme poverty have made combating Ebola more difficult. “The bigger crisis is Ebola plus almost no government. It’s Ebola plus no health system. That’s the real crisis.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Please weigh in on Selanikio’s questions and concerns. Do you think international development agencies have indeed helped the poor? How can we do better? Now in 2015, what are the biggest global health challenges to tackle?

Leave your comments here or send your thoughts to [email protected].

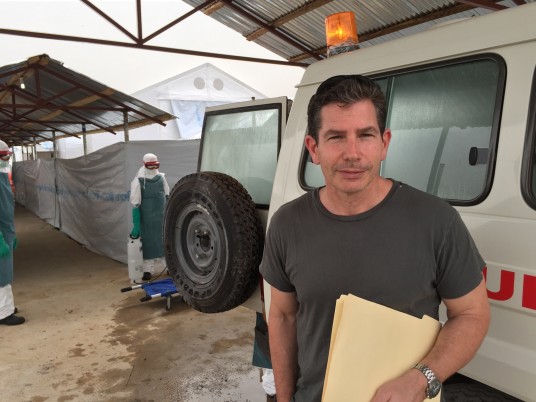

Top image: Medical staff taking reports at a shift change at Lunsar Ebola Treatment Center. (Credit: Selanikio)

Additional Resources

A debate in the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog between Tiny Spark Advisory Board member Chris Blattman and Adia Benton and Kim Yi Dionne over whether International Monetary Fund policies contributed to Ebola’s spread.

Learn about Selanikio’s efforts to bring better data collection to global health through Magpi.

Here’s Selanikio’s 2013 TED talk on the need for more efficient data collection in global health. “There’s a concept people talk about these days called big data,” he says in the video. “But we don’t know for any of the clinics in the developing world, which ones have medicines and which ones don’t. We don’t know how many children were born in Bolivia or Botswana or Bhutan. We don’t know how many kids died last week in any of those countries. We don’t know the needs of the elderly, the mentally ill; for all these critically important areas we want to solve problems in, we don’t know anything at all.” Selanikio argues that more efficient data collection is an important first step to better health interventions:

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mb8x6vLcggc[/youtube]